THEIR SIDE OF THE STORY: Law enforcement leaders and an expert from the Montpelier-based Crime Research Group say the UVM study “Driving While Black or Brown in Vermont” has flawed data.

Since its release in January, the traffic stop study “Driving While Black and Brown in Vermont,” by UVM economics professor Stephanie Seguino, has been a blot on the reputation of state and local law enforcement.

The report’s title — and assertion that Vermont police stop minorities in disproportionately high numbers — insinuate that Vermont police are out to get black and brown people, either consciously or subconsciously.

But local police and at least one crime research expert are expressing doubts about the validity of the report.

“I think that [Seguino] has done a good job of bringing the issue to the forefront — of like, ‘let’s talk about how people are experiencing their interactions with the police’ — but I wouldn’t draw any conclusions from [the report],” said Robin Weber, J.D./Ph.D.

Weber serves as director of research for the Crime Research Group, a Montpelier-based nonprofit research center for criminal and juvenile justice.

“The census methodology that Dr. Seguino is using is not appropriate. And you combine that with the data quality issues, the duplicates, officers being inconsistent on how they do searches, and all that sort of stuff, I don’t have faith for those reasons,” she said.

The duplicates to which Weber refers relate to when an officer gives someone multiple warnings in one traffic stop. Each of those warnings lists the race of the driver, which gets recorded as another stop.

“She [Seguino] doesn’t fix the duplicates, which is a problem when you are looking at a really small population of minorities,” Weber said.

The problem with data from contraband searches, Weber says, is some officers were only recording race data on contraband for the driver and others were recording data if contraband was found in the car.

“That gets at what some of the police concerns are. There was no state-wide training when this was rolled out [in 2014],” she said.

In another possible oversight, the study doesn’t account for the states and license plates of the drivers who were pulled over, or the major highways on which they may have traveled while passing through.

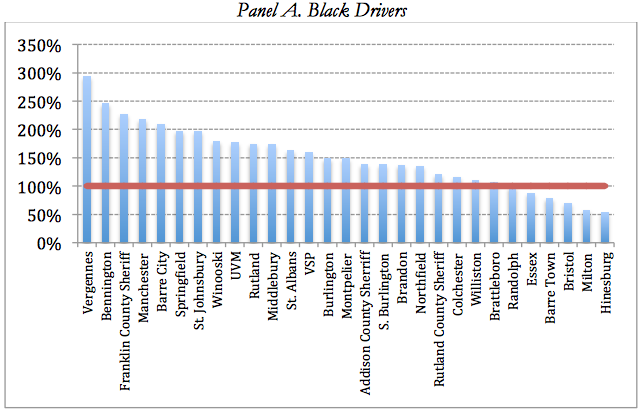

Bennington and Vergennes, the study’s most suspect locations for racial disparities in policing, have major state road Route 7 passing through or nearby respectively. Franklin County and Barre City, also high in stopping black drivers, have Interstate 89.

Likewise Springfield and St. Johnsbury have Interstate 91, continuing a pattern that suggests the issue may not be the race of drivers, but rather the travel patterns of minorities using the state’s major highways.

A key claim of Seguino’s report is that the rate of minorities getting pulled over in these areas is disproportionately higher than the percentage of minorities in the local driver population.

ACCURATE?: This chart from “Driving While Black and Brown in Vermont” claims to show the likelihood of a traffic stop compared to the share of population by race. The vertical bars represent the share of black drivers stopped by the local agency divided by the county black share of the driving population, based on ACS or DMV estimates.

When the report was released in January, Bennington Police Chief Paul Doucette observed that his town has major roadways connecting to New York and Massachusetts — a key point left out of the study. He added that police look for traffic violations, not race.

“I believe that there’s a lot more to this than looking at people who were searched and who received a ticket,” he told the Berkshire Eagle. “If someone violates the law, we take action. We look for violations, we’re not actively looking for people’s race.”

This week, Barre Deputy Chief of Police Larry Eastman told True North that failing to account for travel patterns of major roads leads to wrong conclusions.

“If you have major roadways you are not going to get an accurate depiction of that data,” Eastman said in an interview. “It’s foolish to think that if we stop a car in Barre City it’s a resident in Barre City every time.”

Weber has additional concerns about the study’s data on Bennington.

“In Bennington County [Seguino] uses the DMV data, so the non-at-fault driver data in two-person crashes. This is problematic in a few ways — one, is race was missing in 35 percent of the cases,” Weber said.

The other matter, according to Weber, is auto accidents typically have hot spots in town, and if data is not collected from those spots then it doesn’t represent local drivers.

“She’s using the driver population of not-at-fault drivers for the entire county for a particular town, which is also not appropriate methodology,” Weber said.

Seguino could not be reached for an interview in time for publication, but she defended her work in general comments emailed to True North.

“There are no flaws in methodology. A previous study on Burlington, Winooski, UVM and S. Burlington that uses the methodology of this paper was peer reviewed by academics who do work on racial disparities in policing [and] found the methodology and empirical results to be sound,” she wrote.

She also addressed using the accident reports for driver data.

“It is a better estimate of who is on the road, regardless of the state the vehicle is from,” she said.

Manchester Chief of Police Michael Hall says his department got a bad rap from the study. He took issue with the small data sizes, such as the use of just a half dozen traffic stops of minorities over a few years’ time.

“It would be pretty evident if you had an officer racially profiling,” Hall said. “We would be aware of it and we would see it in internal stats.”

He said the media should be more careful with these studies before reporting them as fact.

“I don’t think it serves anybody a good service to just have the media take these things and run with them,” he said.

The report “Driving While Black and Brown in Vermont” can be read online here.

Michael Bielawski is a reporter for True North Reports. Send him news tips at bielawski82@yahoo.com and follow him on Twitter @TrueNorthMikeB.

I maintained a changeable letter sign board for many years at my business. Half for business, and half for public service.

The message that brought the hottest response was a fact;

CRIME PHOTOS SHOW SOME VT DIVERSITY a fact, unfortunate fact.

Two scathing letters to paper, followed by so many in support that the paper announced it would print no more letters supporting Mr Richmond’s sign !!

I would ask, if a ‘diverse person is arrested for drugs or burglary or assault, and the Diverse are 10%? of our population, then does that require that no more diverse persons can be arrested until 9 Evil White persons are arrested?

Creative Statistics ?

The question I keep having is what percentage of the traffic stops were for a legitimate reason ? If the traffic stop was valid, then the race of the occupants is irrelevant. How can a police officer know the race of the driver in advance of the stop, especially if he (or she) has been following the subject vehicle, he (or she) would know the make and model of the vehicle, he (or she) would know the state where the vehicle is registered, he (or she) could “run” the plate and learn whether the vehicle is flagged for violations or whether the owner has outstanding “issues” and could observe any visual violations such as equipment defects (burnt out lights, emissions, body damage, . . .) – of course none of these would relate to discrimination or bias – just good police work.

Further, Chief Eastman’s observation as to traffic patterns and local statistics is certainly a valid explanation for the variables – note the locations with the greatest disparities are mostly locations with where the interstate traffic, border crossings and college student (not included in the census statistics) would impact the figures – Barre, Bennington, Brattleboro, Burlington, Middlebury, Montpelier, Rutland, St. Albans, St. Johnsbury, Springfield, Vergennes and Winooski.

I think the conclusion that police, especially the State Police, are targeting minorities is a manufactured conclusion, that is “study” where the researcher determines the desired result and THEN collects data to prove that result.

I totally agree, I tend to believe that police make stops when there is a reason to.